| The Cottages, erected on the west side of Third Avenue between 77th and 78th streets in 1936-37, is a most unusual example of the building ty~pe known as the taxpayer. The Cottages form an extraordinary complex. They are a unique urban design concept that has long been recognized as a significant. The building was planned to combine commercial and residential uses; its design melds traditional architectural forms with technologically-advanced materials; its concept reflects a sensitive response to urban conditions on Third Avenue in the 1930s when the noise and shadow of an elevated railroad blighted the street; and the project reflects an important historical movement in New York City's real estate evolution as buildings were designed in response to the increasing lure of the suburbs. |  |

Yorkville, the area of the Upper East Side located east of Lexington Avenue, was developed from open land into a middle- and working-class residential neighborhood beginning in the 1860s when a few rowhouses and tenements rose on the streets convenient to horsecar lines on Second and Third avenues. Development was interrupted by the financial panic in 1873 which brought most local building to a stop. However, following the inauguration of service on the elevated rail lines on Third Avenue in 1878 and on Second Avenue in 1880, construction boomed. The elevated lines contributed significantly to neighborhood development, permitting people to live in neighborhoods such as the Upper East Side that were distant from the city's business and commercial districts. These rail lines also had a negative impact on the streets where they ran. Thoroughfares such as Third Avenue were permanently in shadow and the noise of the trains and the dirt, smoke, and cinders discharged by their engines made life on these streets unpleasant.

|

Third Avenue was a commercial thoroughfare that was lined with four- and five-story tenements, each of which included a ground-floor shop, with modest apartments above that were rented primarily to the Central European immigrants~who settled in Yorkville in the final decades of the nineteenth century. The blockfront on the west side of Third Avenue between 77th and 78th streets, with its eight four-story tenements with storefronts at street level, typified this development. These crowded tenements and the noisy elevated lines created an environment in Yorkville that contrasted dramatically with the rowhouses, mansions, and apartment buildings housing many of New York's most affluent households, located only a few blocks to the west, from Fifth Avenue to Park Avenue. |

In the 1920s, conditions in Yorkville and on the Upper East Side began to change. The Yorkville area was so convenient to the new skyscraper center developing on the streets surrounding Grand Central Terminal that it was only a matter of time before affluent households recognized the value of living in this neighborhood. In addition, by the 1920s, most wealthy people found the large townhouses and mansions built at the turn of the century to be too expensive to maintain. Many moved into the apartment houses rising on Fifth Avenue, Park Avenue, and nearby streets. A large number of other city residents moved out of New York City entirely, settling in such rapidly developing suburban communities as Bronxville and Scarsdale. Wealthy people who did not wish to live in an apartment house and were not interested in suburban life began to purchase or rent the small, inexpensive rowhouses in the blighted but convenient East Midtown and Yorkville neighborhoods. In the 1920s, certain blocks from the upper East 40s through the East 70s, east of Lexington Avenue, were transformed into fashionable residential enclaves. The Turtle Bay Gardens Historic District on East 48th and East 49th streets between Second and Third avenues, the Treadwell Farm Historic District on East 61st and East 62nd streets between Second and Third avenues, and the block of East 63rd Street between Lexington and Third avenues are examples of this development.

The onset of the Great Depression in 1929 slowed the rehabilitation of Yorkville. Owners of Yorkville tenements were faced with a dilemma since their aging, often sub-standard buildings were expensive to maintain and, as immigration slowed, increasingly difficult to rent. New building codes required substantial changes to the buildings, entailing costs that would not necessarily be recouped from limited rent rolls. Some owners modernized and upgraded their tenements in an effort to continue the gentrification of the neighborhood. They added amenities such as fireplaces and modern kitchens and baths to the small tenement apartments and beautifully laid out landscaped gardens, in order to attract middle-class, generally single residents. Other owners simply chose to demolish their economically troublesome tenement buildings and erect one- or two-story commercial buildings, known as taxpayers, in their place. Taxpayers were generally planned as temporary structures that would provide enough income to the owner to pay taxes until~ economic conditions improved and a larger and more profitable building could be erected. It is within this context that the Cottages were erected, combining the taxpayer apartments and landscaped garden found in the revitalization projects.

| The tenements on the west side of Third Avenue between East 77th and 78th streets were owned by the Goelets, an old New York family that had played an active role in real estate and building since the 1880s. Robert Walton Goelet, who ran the family's real estate empire, decided to demolish the Third Avenue tenements and replace them with a unique taxpayer complex. The new two-story building was to have shops on the ground floor with apartments above. Goelet did not intend that his new building would be a homely commercial structure with pedestrian apartments. Instead, Goelet and his architect/engineer Edward H. Faile created a superb environment that is a surprise to even the most jaded New Yorker. |  |

Robert Goelet had worked with Edward Faile on a previous project -- the landmarked Goelet Building on Fifth Avenue at West 49th Street. The Fifth Avenue building has striking exterior stonework and a novel structural system conforming to the building's dual use as shops and offices. The Cottages are a no less innovative project combining shops, apartments, and a terraced garden. The exterior on Third Avenue is quite Modern in its design, with simple massing and extensive use of machine-made materials. As was typical of taxpayers, the ground floor of the Third Avenue elevation of the Cottages was built for shops. The shopfronts were quite up-to-date, with large expanses of plate glass, a striking frieze of milky glass (in a New Yorker article, Lewis Mumford referred to it as "mottled lilac-colored glass"), and projecting rounded corner canopies, sheathed in metal and supported by columns. Architectural Forum noted in February 1937 that such "glossy" materials were chosen for the facades of taxpayers in order to attract attention to the buildings and draw people into the shops. Although some of the "lilac-colored" glass has been painted and other sections are covered by signs, the shopfronts are surprising intact.

The second story of the Third Avenue frontage is faced with red brick articulated simply by large rectangular openings, some filled entirely with glass blocks and others filled with glass blocks and steel casement windows. At first glance this is a curious design; the use of this second story is not immediately apparent. Since very few taxpayers were designed with residential units (this may be the only one), one does not expect apartments set above the stores, yet that is what was designed for this floor. In order to maintain the uniformity of the Third Avenue commercial frontage and not encumber any of the valuable rental space with stairs, the entrance to the residential units is from the rear. The original entry gate and a modest gate house were located on East 78th Street.

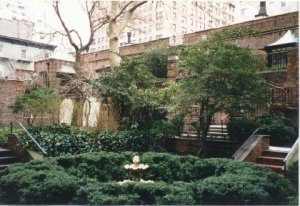

Although located only a few feet from busy Third Avenue, with its shadowy elevated railroad, the residential complex created by Goelet and Faile is one of the most extraordinary environments in New York. Since the entire ground floor of the building is devoted to stores, the Cottages (actually one-bedroom apartments) are located on the second level, set back on a terrace reached by flights of stairs from the garden on 78th Street. The concrete slab terrace was covered with 18 inches of top soil and stone pavers and it was beautifully planted. In contrast to the Modernism of the street elevation, the rear of the Cottages, with its eight residential units, takes the form of a landscaped, English Regency row. Each apartment has a smallprojecting vestibule with multi-paned windows and a concave Regency-inspired roof; the stairs and roofline are ornamented with delicate iron railings of a type that might be found in Cheltenham or other Regency-era English towns, and the brick in this residential portion of the building was originally painted white as were many Regency house fronts.

The creation of a residential complex focusing on a landscaped garden reserved for the common enjoyment of all tenants was a development of the 1920s and 1930s and was, in part, a response to the lure of suburban living, where families could purchase houses in traditional styles (including English Regency) that had landscaped grounds. In New York City, some of the rowhouse rehabilitation projects of the 1920s were designed around interior gardens planned for the use of all tenants, as is evident at the Turtle Bay Gardens Historic District and the MacDougal-Sullivan Gardens Historic District. New apartment house complexes, such as Hudson View Gardens and those in the Jackson Heights Historic District, were also planned with extensive shared open space. The Cottages is the only taxpayer designed in this tradition.

One of the most innovative aspects of the residential portion of the Cottages is the use of glass block for the Third Avenue windows. The noise and dirt of Third Avenue were not conducive to comfortable habitation, yet it was important that as much light enter the apartments as possible and residential building codes required windows of some sort. Thus, Faile chose glass blocks for the windows because they permitted a maximum amount of light to enter each apartment but also deadened the noise of the elevated. Only in the kitchens, where the law required operable sash, were steel casement windows inserted between the glass blocks. Architectural Forum reported in December 1937, "This is the first series of apartments in New York which shows a serious attempt to do something about the elevated trains which rattle by continuously."

German and French designers had experimented with glass building blocks for several decades before the process of creating sealed, hollow glass blocks that could be used as structural members was perfected by the Structural Glass Corporation and the Owens-Illinois Glass Company in the early 1930s. The new glass-block technology was first used in New York City at architect William Lescaze's landmarked home and studio on East 48th Street between Second and Third Avenues in 1933-34. At the Cottages, the glass blocks were Owens-Illinois' Insulux Glass Block, introduced in 1935. According to an Owens-Illinois advertisement of 1940, "Insulux Glass Block is basically a functional material, designed to transmit daylight, insulate effectively and help maintain better control of interior conditions." The blocks could also be molded with patterns, as is evident at the Cottages. The juxtaposition of traditional Regency design on the western elevation to the Cottages with the modern industrial technology of the glass block on the eastern facade is one of the most fascinating attributes of the complex.

Great care and ingenuity are evident in the design of the Cottages and the Goelets were willing to spend money to create an exceptional commercial and residential complex. It is not clear whether the Goelets intended the Cottages as a temporary structure or a permanent part of a larger development. The site of the Cottages did not include just the Third Avenue building but also encompassed extensive land to the rear that was laid out with tennis and badminton courts. Architectural Forum noted that the Cottages were built "with a view to developing the remainder of the plot at a future date." This statement leads to the conclusion that the Cottages themselves were not seen as a temporary building, but as part of a larger future project. This became even more evident in 1941, when the East 77th Street portion of the plot was sold to Sidney and Arthur Diamond and the remainder of the site, including the Cottages, was leased to the Diamonds, who then purchased the property in 1946. The Diamonds erected the apartment house at 177 East 77th Street, an eleven- story building with extensive open terraces and a landscaped garden that extends to East 78th Street (the garden is part of the tax lot that includes the Cottages). The Real Estate Record and Builders Guide commented on August 2, 1941, that the retention of the Cottages "assures complete protection of light and air and guarantees privacy to the terrace suites on the east side" of the East 77th Street apartment building.

The Cottages complex was recognized as significant as soon as it was completed. Architectural Forum featured an article on the building in December 1937, and Lewis Mumford wrote about it in his New Yorker column on April 9, 1938. In more recent years, the Cottages are discussed in Robert Stern, Gregory Gilmartin, and Thomas Mellins' New York 1930, and are featured in several articles by Christopher Gray, who considers the complex "a brilliant piece of ingenuity." The Cottages and their garden have been nominated for landmark designation several times in recent years (in, for example, 1985 and 1988) and were featured in an exhibition of the most endangered buildings on the Upper East Side mounted by the Friends of the Upper East Side Historic Districts. With the exception of the replacement of the original steel-sash casement windows on Third Avenue and the loss of the white paint on the west elevation, the Cottages complex is a remarkably intact survivor. The building is significant in many ways -- in the history of Yorkville, in the history of housing and neighborhood rejuvenation in the 1930s, in the development of the taxpayer concept, and in its melding of traditional and modern design ideas and materials. Most significant, however, is the fact that the Cottages form an extraordinarily beautiful building complex that deserves to be recognized and protected as a designated New York City landmark.

"Apartments 77th Street and 3rd Avenue, New York City," Architectural Forum 67 (December 1937), 510-11.

Gray, Christopher, "The Invisible Clan," Avenue (February 1992), 26-30. Gray, Christopher, "The Low-Rise During the Great Depression, it paid to build short," Avenue, (June/July 1991), 68-71.

Gray, Christopher, "Streetscapes: The Third Avenue 'Cottages' A Cool Low-Rise Oasis In a Hot Development Area," New York Times May 10, 1987, Real Estate Section, p. 14.

Lustbader, Ken, "Upper East Side Most Endangered Buildings," exhibition report (New York: Friends of the Upper East Side Historic Districts, 1992).

Mumford, Lewis, "The Sky Line: Chairs and Shops," The New Yorker, 14(April 9, 1938), 59.

Neumann, Dietrich, Jerry G. Stockbridge, and Bruce S. Kaskel, "Glass Block," in Thomas C. Jester, ed., Twentieth-Century Building Materials: History and Conservation (NY: McGraw- Hill, 1995), pp. 194-99.

New York City Landmarks Preservation Commission, "Goelet Building (now Swiss Center Building) Designation Report," report prepared by Charles Savaae ~New York: Landmarks Preservation Commission 1992).

"A Panel of Taxpayers," Architectural Forum 67 (February 1937), 158-61.

"Private Terraces Prove Primary Renting Inducement," Real Estate Record and Builders Guide, (August 2, 1941), 9.

Stern, Robert A.M., Gregory Gilmartin, and Thomas Mellins, New York 1930: Architecture and Urbanism Between the Two World Wars (NY: Rizzoli, 1987), p. 400.

Return to Save the Cottages and Garden

last revised 4/22/97